Leverage of legal requirements and societal needs in financial shared services

Is it possible by implementing operations of shared services to leverage on business strategies, legal and regulatory functions, IT infrastructures and societal needs? What is the correlation between compliance and sustainability with regard to shared financial services? It is a matter of fact that compliance consists of making sure that legal provisions are observed, but is that enough to make shared services on the one hand safe and on the other hand more efficient? Is it possible to minimize legal risk and to transform structures of sourcing processes in a way that they are innovative and more profitable?

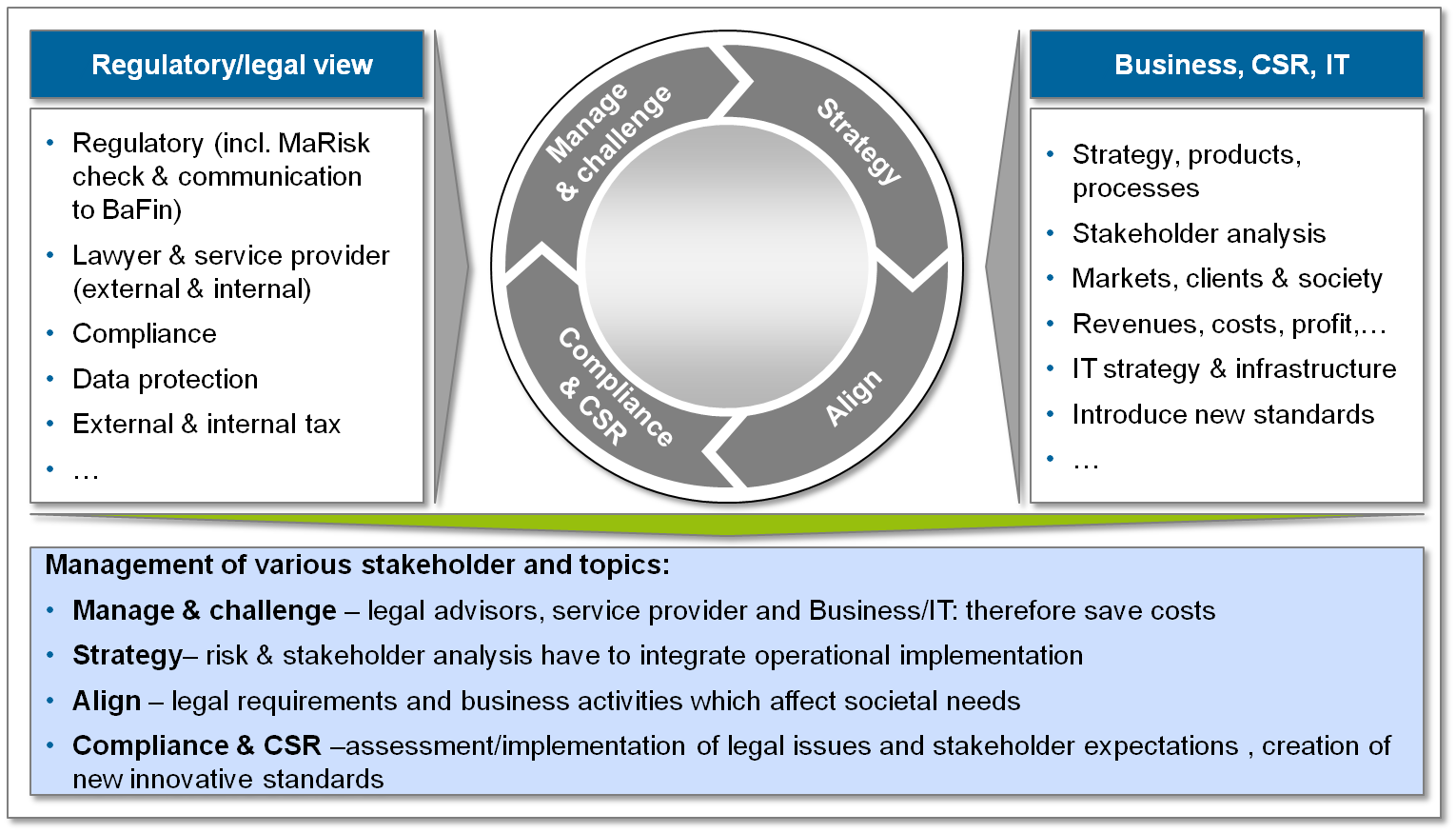

Bringing compliance and CSR (corporate social responsibility) together implies that business models of sourcing and shared services have to observe specific legislative requirements and at the same time have to pay attention to particular groups of persons affected by business operations. What is the connection between law and corporate social responsibility? Legal norms are not merely schemes to be observed ipso facto, but rather the synthesis of divergent interests or in other words the result of political activities, and compliance constitutes their consequent implementation in business. Based on this notion, what happens if financial services providers decide to do “politics” themselves by producing internal frameworks and standards that take care of such interests and offer even more than legislation does? Taking the international context of financial service providers as an example, this proactive approach is innovative because it implies going beyond the “duty of compliance”. Indeed, it focuses on creating processes that, on the one hand, reduce risks arising from different legal systems by enriching the implementation of regulatory requirements and, on the other hand, make clients better off whenever outcomes of services with higher standards are more customer-oriented. Nevertheless, the more sustainability financial service providers will establish, the less regulation will be imposed by the legislator and the easier it will be for banks and customers to actively influence regulation of business and transactions. By doing this, managers of financial institutions have the possibility to use the implementation of legal constraints as basis for a transforming company policy, which implies the adoption of sustainable and society-oriented processes. This last aspect in particular is fundamental for the credibility of the institutions involved. Moreover, procedures based on such approaches might be an object of proper measurement by use of adequate business and societal KPIs.

Structuring of sourcing and shared services

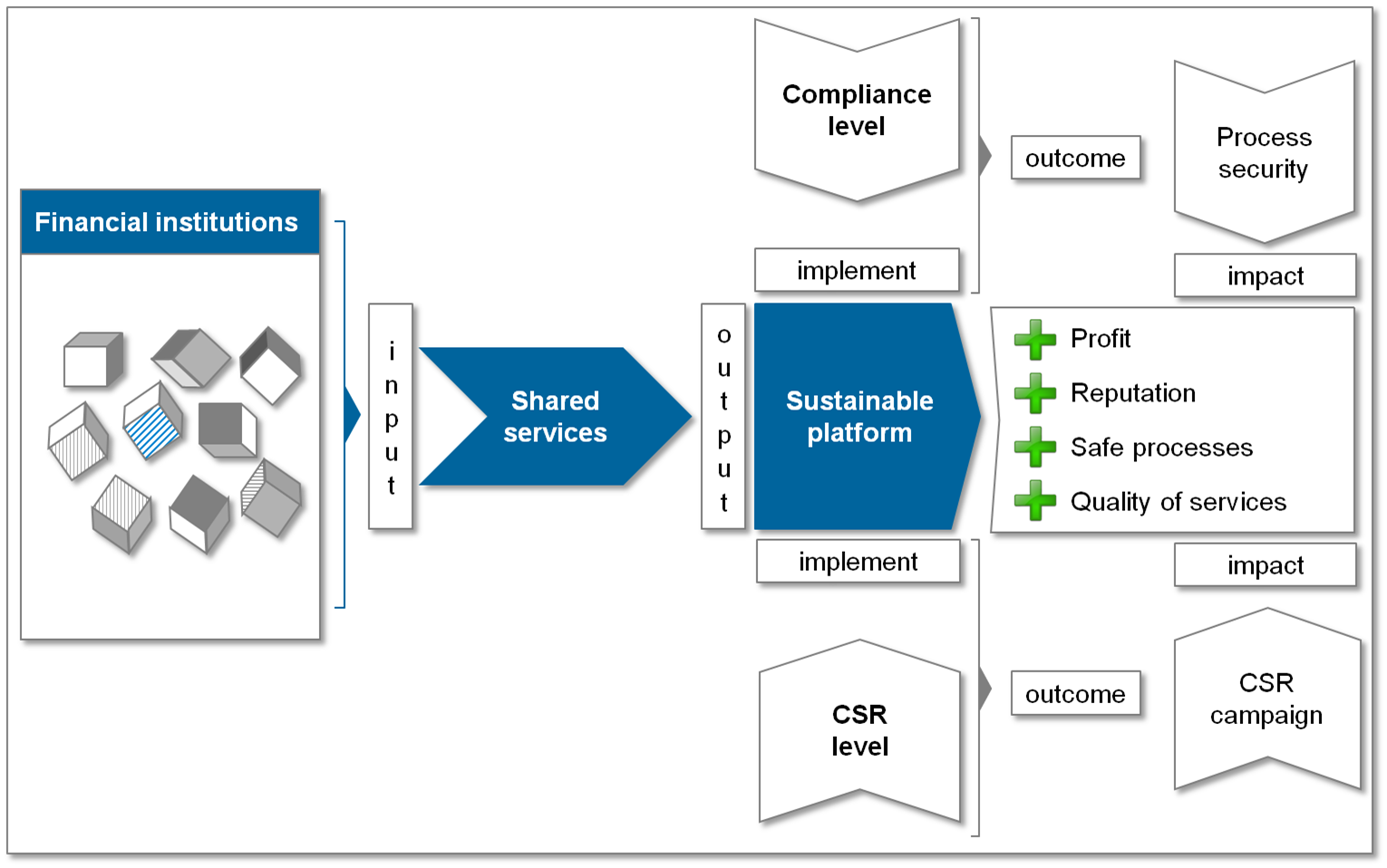

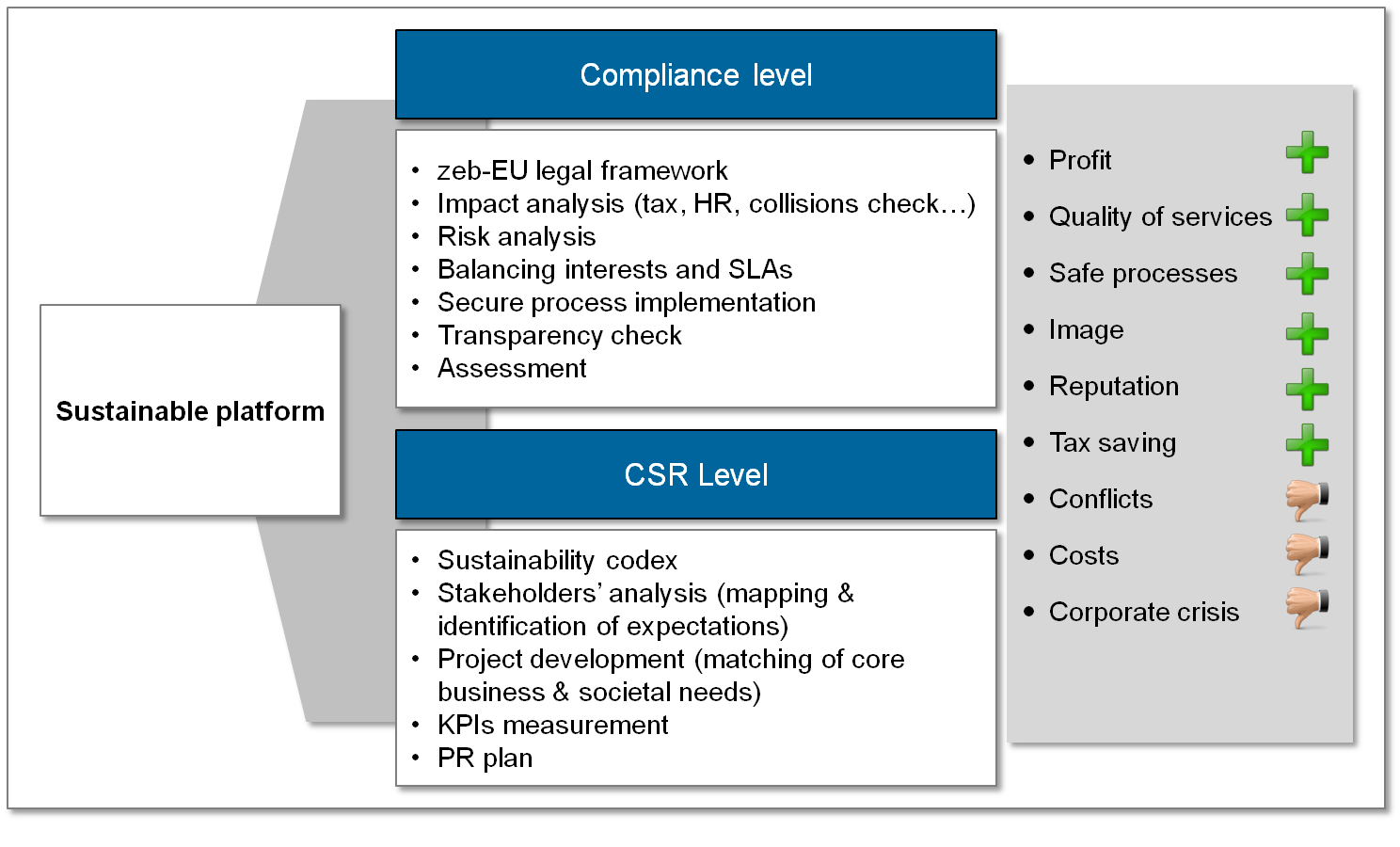

Besides target operating models (TOMs) as a solid basis for solutions in a changing and more complex banking environment, a sustainable platform for value creation in sourcing and shared services is key. The idea behind it is that the “platform” of shared services, in which financial institutions participate mostly through partnerships, is solid both with regard to compliance and with regard to CSR. The compliance system aims to assure process security, while the CSR system delivers campaigns or projects that align the core business to the interests of the stakeholders through sustainable intervention.

The impact of combined actions of the two dimensions offers a decrease in conflicts and at the same time an enhancement of the financial institutions’ reputation, an increase in performance quality and competitiveness and, consequently, an increase in profits. The platform can be integrated into every business activity and due to the sharing of processes and services, transaction costs are reduced and the quality of each single operation is improved at every level.

Specific intervention in a context of lack of uniform regulation in Europe

To make partnerships in shared financial services more efficient, banks need to ensure support across their organizations. Switching from a traditional service model to a shared services model requires not only a remarkable change in mindset and management, but also implies being conscious of how to set legal interests (both particular and of the consortium) and to know what is possible and to what extent. Compliance excellence is the art of mastering legal norms in different environments and at any level. Complying with law reduces costs because it minimizes risks arising from potential conflicts with partners, customers and authorities. Therefore, by implementing operating models, the topic is given importance at each stage of the value chain of financial service providers. However, in practice a number of difficulties arise due to the complexity and scale of the matter.

Typical legal issues in the context of sourcing and sharing services activities arise:

- from the possession of technical infrastructure and IT systems;

- from the legal framework concerning the ownership of certain processes and/or activities;

- with respect to data protection issues and banking secrecy;

- from applying SLAs;

- from structuring governance policy and human capital;

- from managing trust;

- from defining internal and external responsibilities for monitoring and controlling processes;

- from dealing with taxation systems, etc.

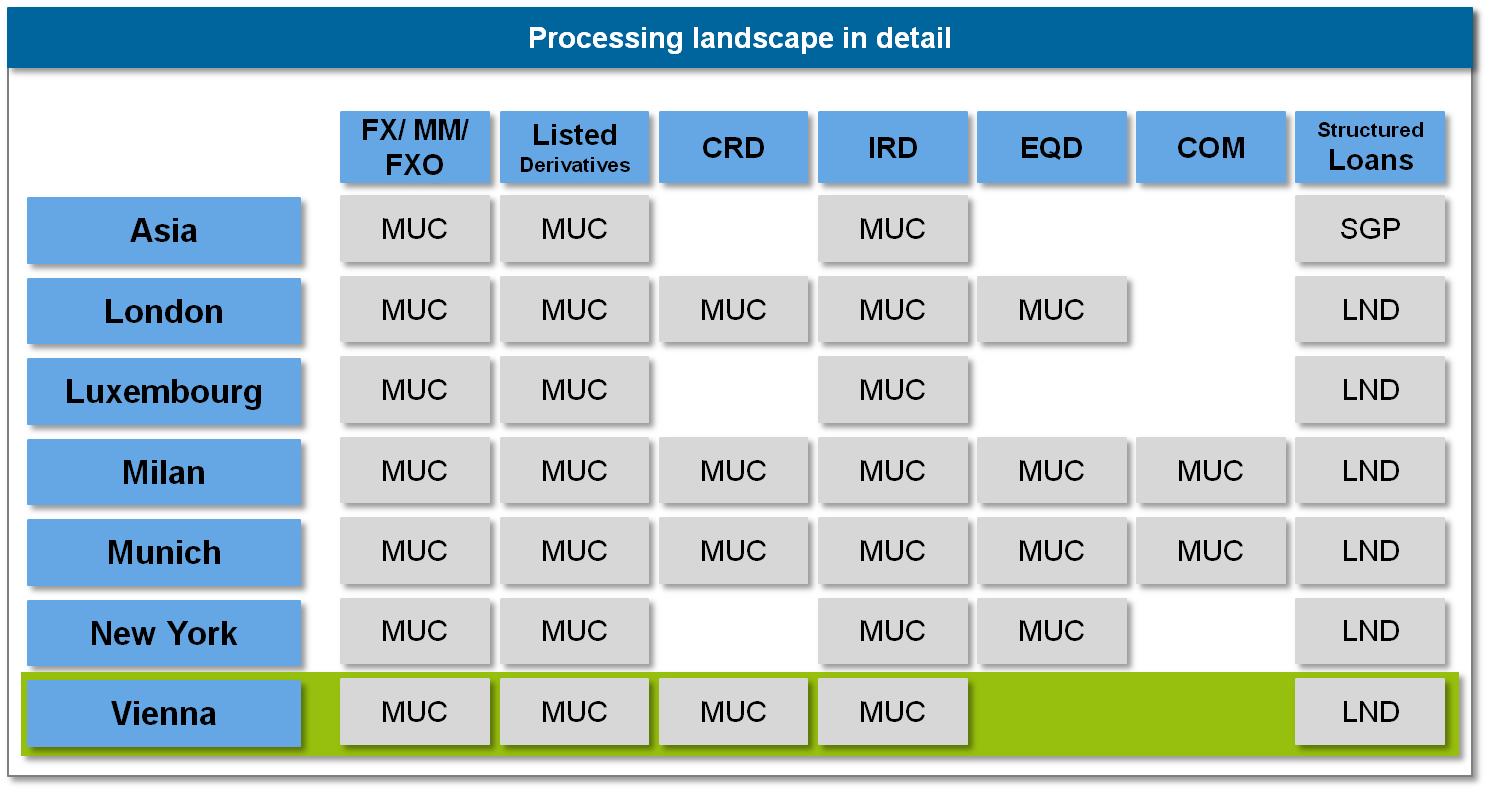

Cross-border activities of financial institutions operating in Europe pose even greater challenges. The topics outsourcing, insourcing and shared services have not yet been explicitly addressed at EU level and the most competitive financial service providers try to be proactive by creating models that do not simply comply with current norms, but are also in line with (possible) future legal constraints. This is a rather challenging undertaking, given that there is no specific and comprehensive EU regulation or directive pertaining to this subject. Here, an understanding of the European legislation and how a particular issue in financial shared services is treated and influences daily operations is crucial and should always be analyzed case by case. From a national perspective, homogeneity is not necessarily the rule either, because norms and powers of competent regulatory authorities often differ between the member states. In some countries, the power to intervene of the competent financial supervisory authority, e.g. the BaFin in Germany, has expanded since 2013. However, the dualism of European and national legislation is only one side of the coin. To make things both more complicated and more interesting for managers, there are further legal requirements to meet when shared services are processed from/to the European Economic Area (EEA) or third countries. In other words, a shared cross-border service must comply with and be checked at several legal and international dimensions that determine the applicable normative framework and consequently the impact on governance and operations. Nevertheless, by implementing sourcing and shared services there are some principles that are opportune to satisfy, for example finding the applicable legal framework, executing a risk analysis and arranging adequate measures to avoid additional risks; do not delegating decision-making powers and control rights; designing control and monitoring offices; deregulating details through SLAs; ensuring transparency of processes.

At a political level, the European Union is currently pushing for legislative frameworks that pay closer attention to sustainability issues in several sectors, including the financial industry (where the concept of sustainability has not yet been properly defined anyway). For this purpose, methods that measure performance, position, effects and transparency of financial institutions are very important to innovative banks. Thus, the next step is to link legal topics to CSR issues in order to create sustainable new standards, and to offer added value that can easily be promoted to the general public. The underlying idea is that business does not only interest financial service providers and clients, but a wider group of stakeholders. Moreover, implementing a sustainability codex and/or CSR projects is a profitable strategy that supports the corporate mission, enhances the corporate reputation and makes it possible to retain existing customers as well as to acquire new ones. This is possible anytime that financial institutions are able to offer innovative services and demonstrate that transforming service providers are much more innovative than classical banks.

Critical aspects and practical problems in the integration of compliance and CSR

The most relevant difficulty regarding the provision of shared financial services is to define proper CSR issues. Moreover, it is not always easy to find the link between these and compliance topics. Chief compliance officers are rather engaged with their normal business and are not familiar with considering CSR topics, because they are not usually the contact person for these (this applies not only for the financial industry). Thus, why should responsible compliance managers care about CSR? Is it not sufficient to simply observe legal and regulatory requirements, to ensure the correctness of services, to design well-structured SLAs and to define adequate monitoring and controlling systems? The answer is yes, if the scope of sourcing financial shared services is limited to implementing just the required minimum.

It is true that compliance is about observing legal norms or, in other words, about implementing legal standards in the operations of a business, whereas the application of sustainability measures in a business enhances the quality of such legal standards. Therefore, the options to choose from are either to purely apply the existing rules to make processes legally secure or to go beyond this on a voluntary basis by implementing innovative and more sophisticated standards, which make processes of banks safer from a legal point of view and more reputable in the eyes of the public. If this approach is applied successfully, it makes sourcing and shared services economically more valuable.

Aligning compliance and CSR under the example of data protection

Sharing and delivering personal information is becoming increasingly important and complex due to the progressive development of IT systems within the financial industry. In Europe, the right to data protection is recognized as a human right, as provided by Article 8 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. In Germany, data protection has been recognized at constitutional level as the “right to informational self-determination” since 1983. In Switzerland, data protection is regulated at federal level and in Italy at national level, while in Austria the topic is closely linked to banking secrecy. Moreover, some countries treat data protection as a matter of either public or private law, while in other countries there is no separation of the subject with regard to such a dualism (e.g. in Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary). With a view to data protection and banking secrecy, the territorial principle applies as a rule. This means that the applicable law is the law of the country where an act or event takes place (e.g. a payment for a service or the generation/delivery of the information). As with any principle, there are, however, some exceptions. Therefore, it is very important to analyze legal questions from a variety of perspectives. What happens if, for example, a French bank sources financial services to Germany or to Austria or to both countries? Does the objective of data protection change? What is the applicable law? What are the effects on business processes? What are the rights and the obligations of service providers and clients? How are responsibilities distributed between business partners? As with any legal issue, in order to answer all these questions it is first of all necessary to identify the applicable law by a collision check and then to describe exactly how data protection is defined and understood there. The objective of European data protection is, however, not the protection of data itself, but rather the protection of the personal rights of those whose data are being processed. For instance, the German Federal Act on data protection (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz, BDSG) provides as follows: “The purpose of this Act is to protect the individual against his/her right to privacy being impaired through the handling of his/her personal data”. Legislation in other European countries comprises very similar regulations. Thus, comprehending the “what” (in this case: the use of personal data) is very important for understanding the “how”, i.e. how to find legal answers to complex questions (e.g. information concerning the extent to which a specific use of personal data in international shared services would be compliant with the applicable law). Furthermore, any legal matter should also be scrutinized in relation to other norms with the aim of making processes secure and ensuring that there is no divergence with regard to other legal systems. For example, while data protection is imposed by act of law, banking secrecy is a product of the contractual relationship between banks and customers. This may give rise to questions, e.g.: Is it possible to derogate from public (international) law through a private contract? In fact, bank secrecy and data protection represent two autonomous entities that are not contrary but rather coexist as long as they do not overlap. Before a financial institution discloses client data to third parties or business partners, it normally has to examine both sets of legal obligations to establish which one is prevalent. Simply put, this constitutes the examination of legal risk of any compliance issue, which can be summarized as the analysis of the applicable legal framework and its effects on business.

Owing to its strong social impact, the topic of data protection definitely meets widespread interest and might affect CSR questions, which, when addressed appropriately, enhance the quality of services and processes. In this respect, compliance and CSR are both measured by means of KPIs, which may bespecifically developed to control processes and improve efficiency and effectiveness of sourcing and shared services. At compliance level, .knowledge of legal frameworks of every country involved is necessary. Indeed, CSR-related questions focus on the stakeholder analysis comprising their identification and the proposition of a stakeholder dialogue in line with compliance and societal issues such as ensuring, e.g., effective cross-border data protection. At this stage, a sustainability codex and/or a CSR campaign could be developed with the aim of adjusting operational processes and corporate citizenship of financial institutions to societal needs on the “platform for value creation”. The focus on compliance and sustainability is a clear win-win situation that leaves all parties —business partners, clients and society— better off.

zeb is able to create a sustainable tailor-made platform both at conceptual and implementation level. Consultants specializing in sourcing and shared services support managers by developing solid structures in keeping with applicable legislation. These structures are designed in a multidimensional way and with a long-term perspective and pursue the final objective of enhancing both, reputation and profits.